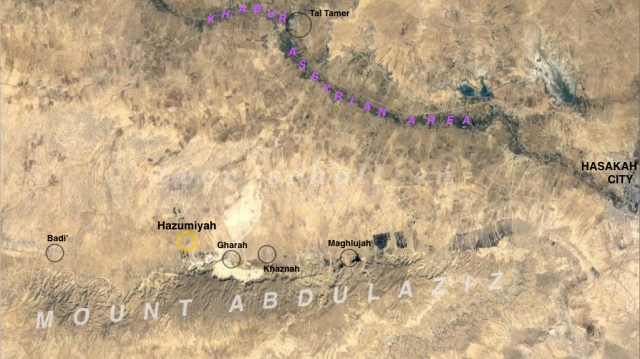

On 27 May, Hawar News Agency published an article covering a “preparatory meeting for the formation of the Armenian Youth Council” which took place in the rural hamlet of al-Hazumiyah, located some 45km west of Hasakah city on the northern slopes of Mount Abdulaziz (referred to in the article as Mount Kizwan, a Kurdish name variant). The article is a wonderful illustration of why I find ANHA to be an enormously rich and irreplaceable repository of so many vibrant details of local life in Jazira and northern Syria, though it may sometimes be belittled by other observers for “pro-PYD” inclinations.

Up until now, I had encountered no record of any presence of the Armenian component of the region in the area of Mt. Abdulaziz, a low limestone ridge rising above the semiarid plains south and west of the Khabur River (mirroring the larger Sinjar range to the east). Indeed, according to research conducted in 2007, the 13,000-15,000 inhabitants of the mountain identify as members of the the Baggarat al-Jabal{1} tribe, “with one exogenous family group, the Sayyad, who live in one single village and have been socially incorporated into” the Baggarah majority {2}. The Baggarat al-Jabal, part of the large but rather fragmentary Baggarah confederation dispersed patchily from the eastern countryside of Aleppo in the west to Jazira in the east and south towards Deir ez-Zor, have lived and moved in the area since the Ottoman era, when they would use the plains below the mountain as winter pastures for their sheep and goats, migrating north to the plains below Tur Abdin in the summer. They also engaged in some small-scale cultivation of cereals along the Khabur during this time, but it was mainly just intended to feed their wandering herds, and mobile lifestyles predominated through to the mid-20th century.

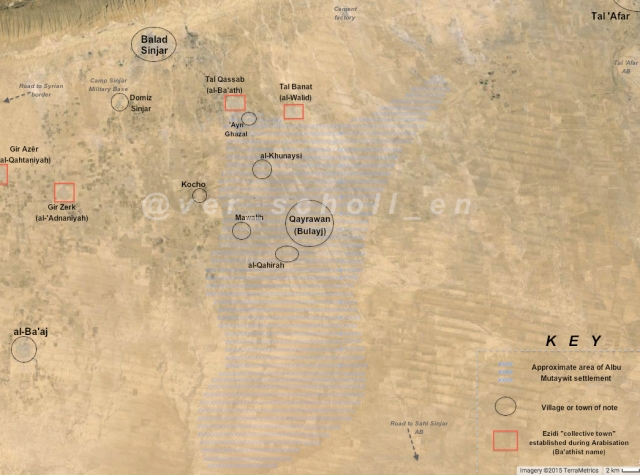

Fig. 1: Map of notable settlements on the northern slopes of Mt. Abdulaziz, with al-Hazumiyah highlighted (expanded view).

The Armenian community in Jazira, meanwhile, traces its formal establishment to the French Mandate (1923-46), when they and other Christian refugees fleeing genocide in Anatolia were invited to settle in the new urban centres and a number of planned rural villages being established by the French to “civilise” and bring under plough the fertile yet nomad-dominated plains. It unlikely that Armenians would have also established themselves around Mt. Abdulaziz at this time, as the first modern settlement of the area (al-Khaznah) was only set down in the 1950s {3}, as independent nationalist governments pushed forward sedentarisation schemes to continue efforts to curb “backwards” nomadism. It is also unlikely that Armenians would have had much reason to settle in the area later, as Mt. Abdulaziz is known to be one of the most impoverished parts of Jazira, with poor agricultural potential exacerbated by land-use restrictions around the mountain’s nature preserves. The only non-urban Christians nearby are the Assyrians living along the Khabur river, who before the war would travel to hold weddings and Akitu (Assyrian New Years’) festivals in the village of Maghlujah near the reforestation projects but never settled around the mountain. Indeed, the Baggarah had been known to mount livestock raids against the Assyrians after they arrived to the area in the late 1930s as refugees of the Simele Massacre and Seyfo before that {4}.

Perhaps it is even misleading to look for visual markers of Christianity as evidence of Armenian identity in Mt. Abdulaziz despite its significance in Armenian culture. ANHA’s photographs of the Armenian Youth Council’s meeting show a seemingly atypical crowd for such an event, featuring many men wearing traditional Arab dishdashas and hijabi women under an outdoor pavilion listening to young people in decidedly more “urban” dress (including the Armenian representative to the Syrian Democratic Youth Council, Eva ‘Issa, wearing no headscarf) [Figs. 2 & 3].

Fig. 2: Villagers of al-Hazumiyah assembled for the Armenian Youth Council preparatory meeting. [ANHA]

Fig 3: Eva ‘Issa, Armenian representative to the Syrian Democratic Youth Council, speaks at the meeting in front of SDYC and Armenian flags. [ANHA]

Satellite imagery of Hazumiyah also shows no structure resembling a church, a traditional cornerstone of Armenian cultural life, in the village—contrast this with imagery of the depopulated village of Hiku (20km south of Darbasiyah), formerly home to a community of Armenians speaking Arabic, Turkish, and Kurdish who fled from genocide in Tal Arman (modern Kızıltepe) in the Mardin plains, which shows a church amongst the few buildings left standing [Figs. 4 & 5].

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Satellite imagery showing identifiable religious buildings in the Jaziran villages of al-Hazumiyah and Hiku.

So what would be the origin of any Armenians in this area that would necessitate such civil society outreach? The lack of reported communal identity other than belonging to the Baggarat al-Jabal tribe and the apparent Muslim faith of the villagers may seem contradictory to this, but may in fact hold the critical clues to solving the mystery.

While the history of modern Armenian settlement in Syrian Jazira may begin in the 1920s, this was actually not the first time when significant numbers of Armenians set foot in the region in the 20th century. Only the decade before as Anatolia was torn apart by genocides of its Christian peoples during the First World War, Jazira became crossed by two major deportation-extermination axes for Armenians expelled from Anatolia: the first coming from Aleppo and Urfa and running along the Berlin-Baghdad Railway (still under construction at the time) and thence through the plains to Mosul, the second running from Diyarbekir and nearby cities through Tur Abdin and Mardin and south along the Khabur River to Deir ez-Zor. These lines intersected at Ras al-‘Ayn, where a concentration camp was set up in the latter half of 1915 and overseen by Chechen gendarmes originally settled there in the late 1860s to curb nomadic dominance of the Jaziran plains and expand cultivation of the fertile banks of the Khabur River.

Fig. 6: Map showing notable locations for the Armenian Genocide in the Deir–Jazira region.

In October 1915, there were reportedly some 50,000 Armenian deportees held in the camp’s 10,000 tents, with regular convoys marched south along the Khabur to the massive deportation hub at Deir ez-Zor, under the administrative authority of which the Ras al-‘Ayn facilities fell. At first, the camps at Ras al-‘Ayn “operated under almost normal conditions” relative to similar facilities, with a death rate of “only 100 a day”; convoys to Deir were conducted “without excessive brutality” and the relatively “well-meaning” local kaymakam even permitted small-scale economic activities and fended off raids from local Arab tribes {5}; among them quite possibly the Baggarah. But a February 1916 visit by the infamous vali of Van, Cevdet Bey, saw the kaymakam replaced with a Young Turk loyalist and the fortunes of the camp turned into abject horror. Preparations were made throughout March of that year for the liquidation of the 40,000 Armenians left in the camp, culminating the following month in bloody massacres at the hands of the Chechens on the banks of the Jirjib, a tributary of the Khabur. Some few survivors made it as far south as the Shaddadi area before being themselves executed {6}.

In summer 1916, the Khabur valley again became the site of widespread atrocities, as Ottoman authorities in Deir initiated plans to exterminate the roughly 200,000 Armenians collected in the camps there. The Chechens of Ras al-‘Ayn, fresh from the massacres there, were dispatched to oversee a total of 21 death marches beginning around 15-16 July. From Deir, the Armenians headed downstream along the Euphrates and after five hours reached the camps at Maratt, where they were stripped of any remaining valuables and separated into smaller groups before being turned north through the desert towards the Khabur; executions and deaths from exposure were regular occurrences along the way. Two days after passing through Maratt, the convoys would reach the camps at Suwar, where the surviving adult males were finally executed and the remaining women and children broken down into yet smaller groups and marched north towards Shaddadi. As the Chechens were not sufficiently numerous to handle the sheer volume of deportees to be liquidated, promises of “plunder” were made to the Arab tribes of the area to encourage them to assist in the killings as the convoys moved deeper into the countryside: the Baggarah between Maratt and Suwar, the ‘Uqaydat between Suwar and Shaddadi, and the Jibbur around Shaddadi {7}.

The areas around Shaddadi were the final execution site for most of those women and children who survived that far in the convoys. A Deiri Armenian descendant of genocide survivors gave the following account:

There is a hill called Markadé, just a two-hour drive from Der-Zor. According to the testimony of Arab desert tribal chiefs, that name was given precisely by the Arabs at the sight of the slaughter of the Armenians. The name “Markada” is derived from the Arabic word “Rakkadda,” which means “countless piled up corpses.” It is said that the said hill had been formed by the corpses of the Armenians. In fact, up till the present day, if you dig the earth a little bit with your hand, you will find the bones of the Armenian martyrs. On that same place the Chapel of St. Harutyun was built, in 1996, on the relics of our martyrs, which are displayed in show-cases in every corner of the chapel.

A little farther, there is a large cave called “Sheddadié.” Again, according to the testimony of Arab desert men, that name derives from the Arabic word “Shedda,” which means “a place of terribly great tragic event.” The elderly Arab desert men relate that the Turk gendarmes had brought the Armenian deportees, had packed them into that large cave, had shut its entrance and had set fire to it. There remained only the bones of the Armenians reduced to ashes…

The etymologies given here for Markadah and Shaddadi are perhaps later inventions: “rakkadda” would rather seem to be connected to connotations of “stagnant” which could plausibly refer to the flow of the Khabur there, and while “shedda” can mean “misfortune” or “calamity”, the name Shaddadi was in use well before the genocide {8}. But even if these recorded meanings are embellished or fictive, that they would be told as such may indicate that the memories of the genocide have been retained and passed down amongst the people who lived around it as it unfolded. The atrocities which occurred there are a matter of historical fact, and the bones of those massacred do indeed still litter the desert areas along this route today (see e.g. this photo essay containing a number of pictures of the mass graves of Ras al-‘Ayn and Markadah).

While sometimes co-opted into the massacres as noted above, Arabs in numerous instances also offered refuge of a kind to those Armenians who managed to escape death in one fashion or another. This phenomenon was fairly widespread, and finds analogy in the histories of the so-called “hidden Armenians” of Turkey. One group of women on the Shaddadi extermination route were reported to have been directly turned over—“probably as booty”—to local Arabs near Hasakah {9}, and some orphaned children were able to flee into the desert to be found and taken in as an honour-bound matter of hospitality and adopted as members of the tribe—or, in the case of the girls, made to marry into the tribe. (It should be mentioned, however, that instances of this have also just as well been called rape and abduction).

Bardig Kouyoumdjian, French-Armenian photographer and descendant of genocide survivors, travelled to eastern Syria in 2001 to find the social traces of these people, encountering descendants and in a few cases elderly individuals who had been rescued as small children. A section of his book Deir Zor, reproduced in translation by the Armenian-Canadian Horizon Weekly, is worth reading in full. He notes the preservation of an Armenian identity amongst many of them in spite of a near total loss of the original culture, language, and religion: “These children of Christians turned Muslim are accepted neither by the Bedouins who are native to the desert nor by the Armenians who have preserved their Christian heritage.” Hearteningly, he also notes a number of members of younger generations “trying to take up the thread again” by learning Armenian or seeking to study in independent Armenia.

ANHA, for its part, mentions nothing of the background of those which the Armenian Youth Council seeks to organise in the village, only recording vague statements by the speakers present. Eva ‘Issa declared that the youth should “restore their lost structures” to reclaim history taken from them by Arabist regimes, while Yusuf Khalawi (also of the Syrian Democratic Youth Council) called the meeting one of “acquaintance and brotherhood”, and spoke of the Baath era as being a time when they were “not able to reach one another”. None of these are particularly specific on the historical details, but Kouyoumdjian did note that the Christian Armenian community of Deir did virtually nothing to connect with their Islamised kin. A priest with him on his journey explained that “that would cause many problems with local Arab populations and would be seen as an attempt to convert Muslims to the Apostolic rite” and that lingering “Bedouin” stigma would render intermarriage unpalatable to urban Christians. The council is slated to be founded at a later date, but in the meantime a list of names of youngsters who would join was drawn up (perhaps suggesting known descent), and plans to teach Armenian in the village were declared.

This is admittedly speculation on my part, as I have not yet found any explicit evidence to confirm, but it is quite possible that the planned formation of an Armenian Youth Council in al-Hazumiyah intends to reach out to local Baggarah tribespeople descended from rescued Armenian escapees. Mt. Abdulaziz lay right along the western side of the Ras al-‘Ayn–Deir ez-Zor line as the atrocities were ongoing, and southerly sections of the Baggarah at the very least would have come into direct contact with the deportees moving north along the Khabur (as mentioned above). Social incorporation and retained memory of escaped and rescued Armenian children and their descendants has been directly documented in eastern Syria by the work of Kouyoumdjian (and surely others), and perhaps with the establishment of this council, the history of the Abdulaziz community will be brought to light as it seeks to fulfil the wishes of those youth desiring to reconnect with their lost roots. I, for one, will be keeping an eye on ANHA for another report…

NOTES AND REFERENCES

{1} Breaking with Chatelard, I use the transliteration “Baggarah” for its noncommittal relation to the discrepant spellings of the tribe’s name in Arabic, found as both البقارة al-baqqārah and البكارة al-bakkārah.

{2} Chatelard, Jebel, 1.

{3} Chatelard, 2.

{4} Dodge, Assyrians, 317.

{5} Kévorkian, Genocide, 651.

{6} Kévorkian, 652.

{7} Kévorkian, 665-666.

{8} For example, the Blunts recorded the placename in their journeys among the Bedouin tribes of the region in the late 1870s, cf. “Faris himself was at a place called Sheddádi, on the Khabur” (Bedouin, 221).

{9} Kévorkian, 666.

PRINT SOURCES

Blunt, Lady Anne & Wilfred Scawen Blunt. Bedouin Tribes of the Euphrates. New York (Harper & Bros.), 1879.

Chatelard, Géraldine.“Jebel Abdel Aziz, socioeconomic assessment.” Unpublished text, 2008.

Dodge, Bayard. “The settlement of the Assyrians on the Khabbur.” Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, 27:3 (1940): 301-320.

Kévorkian, Raymond. The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London & New York (I.B. Tauris), 2011.